The OTHER Most Important Number on Your Dive Computer

The OTHER Most Important Number on Your Dive Computer

What a great time to be a scuba diver! Technological advancements over the last few decades have made diving much easier, safer, more comfortable, and maybe even more fun than it was for our parents’ (or grandparents’) generation. They had to wear a clunky, dangerous weight belt to get under water, while we wear comfortable, safe, weight-integrated BCs. They used big double-hose regulators that breathed hard in certain positions and free-flowed any time they took it out of their mouths. We enjoy balanced (sometimes even overbalanced) single-hose regs that breathe just as effortlessly at 100’ as they do at 10’. And while they basically threw a dart at a board regarding their inert gas loading safety by using dive tables, we get the benefit of MUCH safer dives, with longer bottom times and shorter surface intervals, by using one of the greatest inventions in the world of scuba diving: the dive computer. But you remember that movie where a teenager gained super strength, speed, and the ability to stick to walls, then his uncle tells him, “With great power comes great responsibility…”? Never was that any truer than when using a dive computer.

So, why is a computer SO much better than tables? Unlike tables that round off depth every ten feet and dive times every few minutes, a computer is real time; it’s on your person, tracking what you’re doing, when you’re doing it. Dive computers can show you pretty much everything you would want to know about your dive, but all that info is useless if you don’t look at it and process it once in a while. Sure, there’s a lot of information on a computer’s screen, but you don’t have to digest it all at once. Some of it (water temperature, max depth reached, dive number, interval between dives, etc.) can even wait until you log it later. But there are TWO numbers on that screen (if your computer’s air integrated) to which you’d better be paying close attention…

There are two factors that limit our time underwater: the amount of breathing gas in our cylinder and…..(drum roll, please)…..our NDLs. What are these NDLs I speak of, you ask? First of all, I sincerely hope you didn’t just ask that. Second, NDL stands for No Decompression Limit. Your computer may call it NDL, No Deco, No Stop Time, or something similar. And it’s the other most important number on your computer. In the case of non-air integrated computers, it’s THE most important. I had no idea that there was any confusion about this or that it was necessary for me to write this article. NDLs are Open Water Diver Chapter 1 stuff. And yet, it’s come to my attention that there are quite a few divers out there who have no idea what NDLs are, why they’re so important, and why they need to pay attention to their freaking computers!

Over the course of numerous dive trips, I’ve actually had a few occasions when friends/customers have bent their computers (not themselves, fortunately) while on regular, recreational, reef dives. By “bent their computers” I mean exceeded their NDLs, which put their computers into deco, then did NOT do the required deco obligation. Their computers promptly locked them out, and they couldn’t dive for 24 hours. This made them a little unhappy, in case you were wondering. When I asked them, “How the bloody bull snot did that happen? Weren’t you watching your NDLs??” they said to me, “What the heck are NDLs?? This thing tells me how much air I have.” Yes, they did. They said that. I kid you not. They apparently paid close to $1000 for a color screen, rechargeable, Bluetooth-enabled, haptic alarm-havin’ SPG. As a poor scuba instructor, I’m a bit more frugal and have rarely paid over about $130 for my SPGs.

So, what does No Decompression Limit mean, and why is it important? Remember that gas supply is only one thing that limits our dive time. The other is inert gas loading. In recreational diving that inert gas is usually nitrogen, as it makes up 79% of air. Your body does not metabolize nitrogen, so it’s simply packed away in your tissues. The deeper you dive and the longer you stay there, the more nitrogen gets packed away. And the faster your NDLs tick away. But so long as you stay WITHIN those NDLs and do a safe ascent before they run out (and a safety stop), the excess nitrogen will come out of your tissues in an orderly fashion and make it to your lungs to be exhaled.

If, for some reason, you ignore your NDLs, the next time you look at your computer it may very well say DECO in big letters on the screen. This is still not a huge deal so long as you do what it says to do. Simply follow the computer’s instructions. It will show you the depth(s) you need to stop at and for how long. An example might be something like this: ascend to 40 feet for one minute, 30 feet for 2 minutes, 20 feet for 3 minutes, then do your safety stop like normal at 15 feet for 3 minutes (a little longer wouldn’t be a bad idea in this instance…). Imagine, something as simple as that to increase your safety margin and allow you to keep diving. If you’re worried about having enough breathing gas to complete a short series of deco stops, grab your buddy or the divemaster to come with you. Just don’t get bent. It’s no joke. I know of many divers who have been badly bent in the past who say that they’d rather drown than go through that again. Seriously.

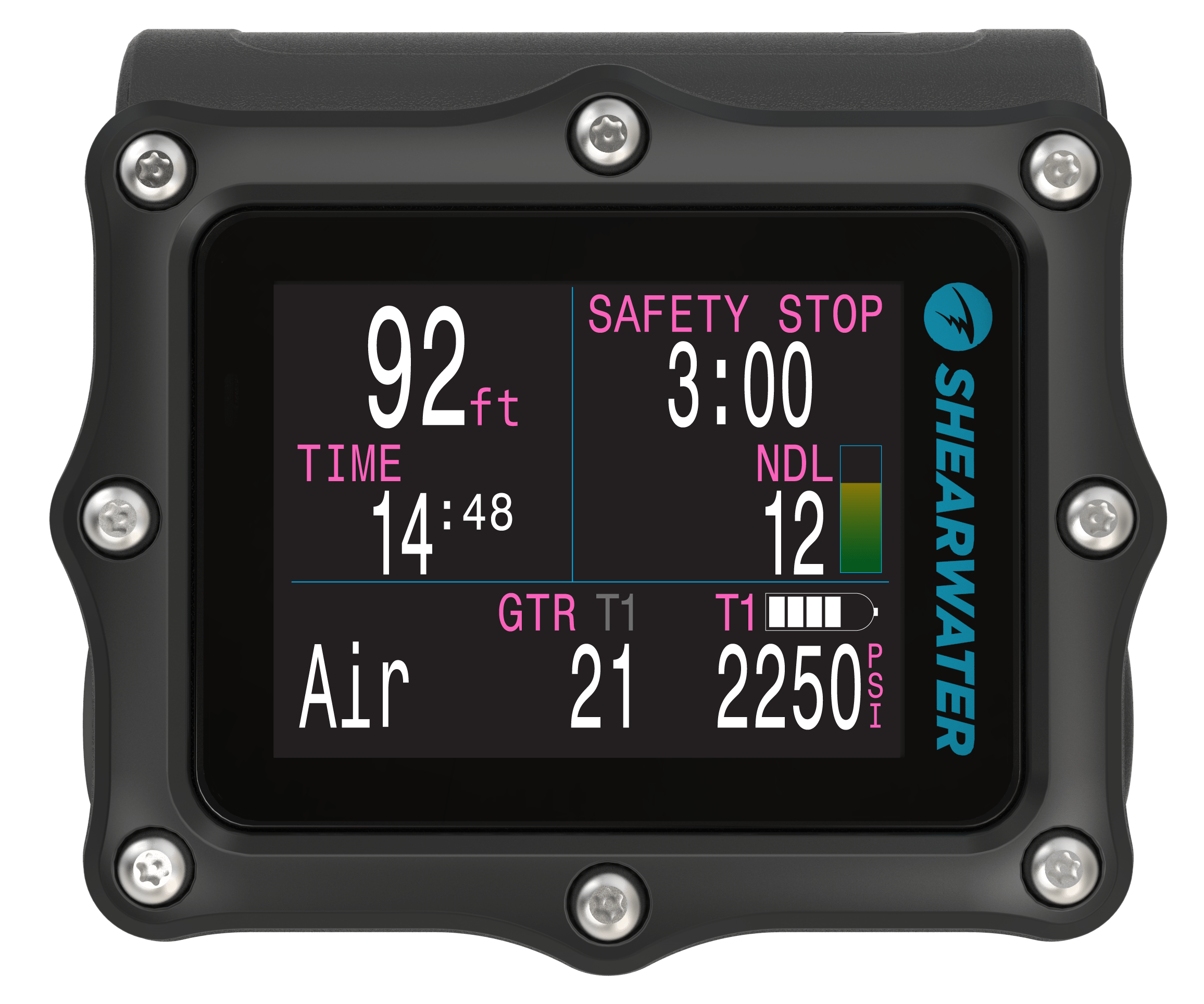

How do you avoid all this in the first place? Well, how do you avoid low-on-air or out-of-air situations? You watch your SPG or air-integrated computer! I’ll bet almost none of you have ever run out of air underwater. Hmmm, guess that technique works, huh? So, simply checking your NDLs every time you glance at your computer will do the same thing. You check the fuel gauge in your car pretty regularly, right? That’s your car’s SPG, but it’s not the only gauge on the dash, is it? You have to give the other ones (speedo, tach, oil pressure, water temp, etc.) a glance now and then too in order to drive safely and keep your car in good running order. A dive computer is no different. Yes, there’s a lot of information on the screen, and some of it isn’t exactly of dire importance. But every single time you look at your computer during a dive, you should be noting at a minimum your depth, dive time, NDL, and gas pressure, if so equipped. Not sure what some of the numbers mean or whether they’re the important ones? ASK! There’s no excuse for not knowing how your dive equipment works. And knowing how your dive computer works could mean the difference between a nice airplane ride back home after a fantastic vacation and a not-so-nice ride in a recompression chamber fighting for your life.

Sorry for the soapbox; had to be said. Until next time, never stop learning, never settle for “good enough,” and stay sharky, my friends!

Dive computers can be a wealth of information.

A Matter of Priorities

Modern dive computers display a LOT of information; you just need to remember to look at the important stuff from time to time. If all you’re watching on this computer is your gas pressure, you’re headed for trouble. At this depth, the diver has 21 minutes of gas time remaining, but only 12 minutes of NDLs.

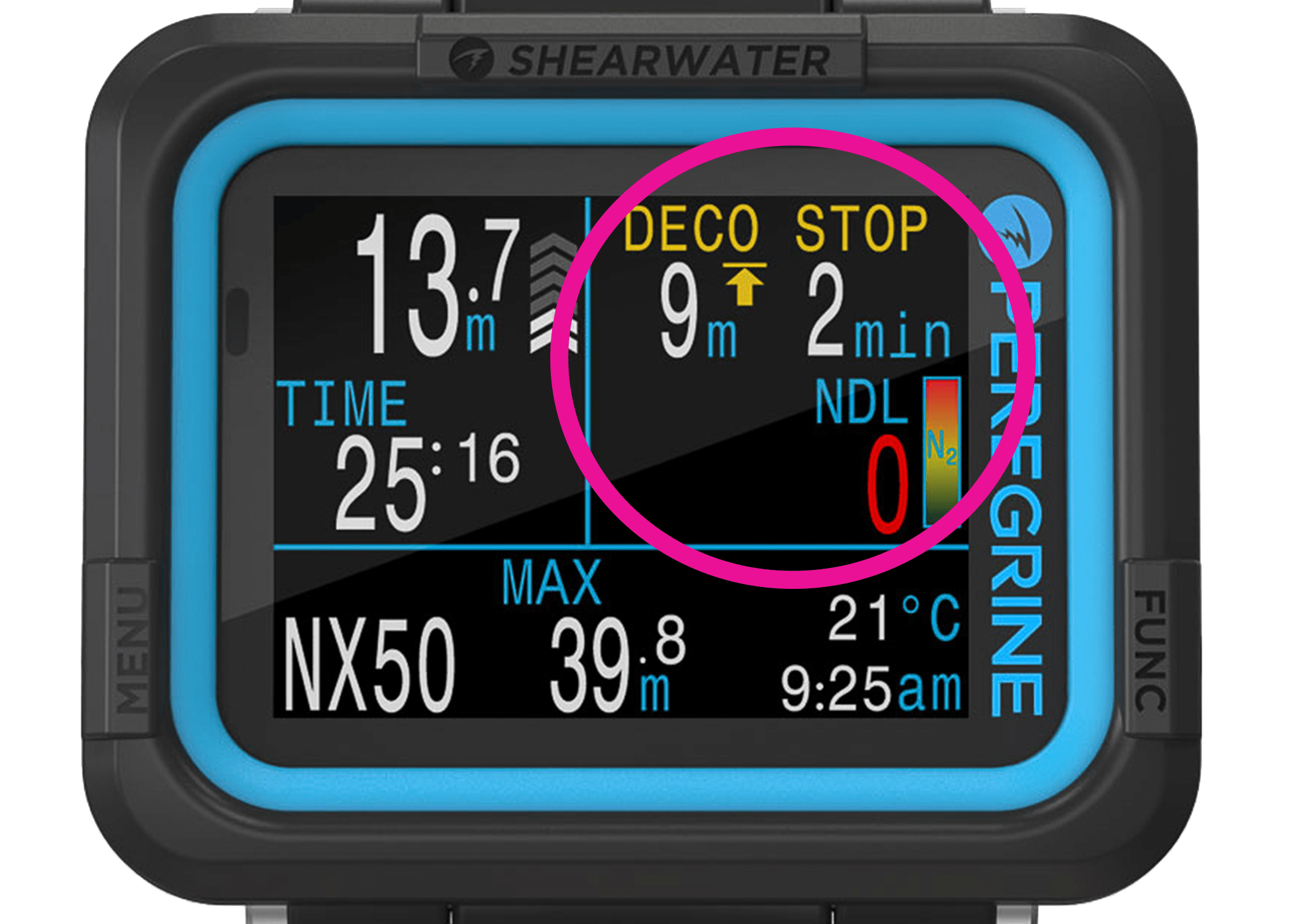

What You DON'T Want

You really don’t want to see your NDLs in the single digits, much less zero. But if you’ll notice above the NDLs, the computer is telling the wearer exactly what to do. Go up to 9 meters and hang out for 2 minutes. Following these directions are what will keep you from getting seriously hurt or, at the very least, locking out your computer (and your diving) for 24 hours.

Consider a Switch...?

If you’ve been diving a console computer, you might consider switching to a modern wrist-mount model. No joke, you’ll look at it more often…

Equipment Specialist

If you’re unsure about the operation of your dive computer, or any of your gear for that matter, PADI’s Equipment Specialist course is something you should really consider. Contact us about upcoming classes!