Perfect Your Buoyancy

If you’ve been scuba diving more than 20 minutes or so, you’ve learned that there’s no more important skill in all of diving than buoyancy. Regardless of how long you’ve been scuba diving, you’ve probably also learned that there’s no more difficult skill to master in all of diving than… yep, buoyancy. It’s something you never quit working on and practicing, and yet true mastery is something that eludes many of us for the majority, if not the entirety, of our diving lives. And by mastery, I don’t mean being comfortable drifting alongside a reef at roughly the same depth, rising a couple feet when you inhale and falling a couple feet when you exhale. I mean that ability to hang motionless in the water, no kicking or hand sculling, perfectly horizontal, a foot off the bottom while you take 27 shots of the same seahorse to make sure the lighting and composition are perfect, without ever worrying about touching bottom…all while breathing normally. Normally is a key factor here; we’ll get into that in a bit.

We all know the basics of buoyancy; we learned those in the Open Water course. Let’s review a few points:

- Weight yourself so that you float at eye level with an empty BC and holding a normal breath, then sink slowly when you exhale.

- If you did the above test with a full cylinder, add four pounds. Most manuals say five, but how do you divide that equally? Seen many ½ pound weights lying around? Me neither.

- Trim yourself out as horizontally as possible in the water, and kick only when necessary to conserve energy and breathing gas.

- Streamline both yourself and your equipment configuration to improve your hydrodynamics, which will conserve energy and breathing gas. It will also protect the underwater environment from damage by your “danglies.”

- Add gas to your BC in small amounts as you descend to account for loss of buoyancy caused by the compression of your wetsuit/drysuit and gas already in your BC. When you ascend, release gas from your BC in small amounts to account for increased buoyancy caused by expansion of your wetsuit/drysuit and gas in your BC.

- When you’re neutrally buoyant, you should rise slightly when you inhale and sink slightly when you exhale.

Okay, all that should sound pretty familiar. I wonder how many of you still do Point 1 whenever you change water type or wetsuit thickness… Probably none. Anyway, moving on. Let’s focus on Point 6 for a minute. Remember your neutral buoyancy exercise in your Open Water course? Your instructor may have called it the “Fin Pivot.” Remember how far you swung up when you inhaled and how far down you went when you exhaled? Remember how hard it was to hover in only 8-10 feet of water without touching the bottom or breaking the surface? It has to bring a slightly smug smirk to your face to think of how far you’ve come and improved since then. And you’ve earned that smirk! Now, let’s try to take you to the next level.

For a while now I’ve been doing something a little different, and it’s been working wonders. I call it “Trimming Out On Empty;” in other words, adjusting my BC (and drysuit, if I’m using one) to make me neutrally buoyant with completely empty lungs. Trying this was born of my frustration with the inadequacies of standard buoyancy techniques and teachings. There are many diving situations where I like to be as close to the bottom as possible – taking pictures, looking for tiny critters, navigating a tight restriction, etc. As you might guess, “sinking slightly when you exhale” doesn’t work too well when you’re only a foot off the bottom. In the process of “breathing normally,” I’d find myself having to inhale when I wasn’t really needing to inhale metabolically, just to keep from contacting the bottom. I’m willing to bet you’ve encountered the same situation and may not have even though much about it. So, maybe breathing normally is to blame? Wait…what?! How can breathing normally be a bad thing? Different question: what is “normal?”

How are you breathing right now? I know, it’s not something you usually think about, but check yourself while you’re reading this article. Are you slowly sucking in everything your lungs will possibly hold, slowly breathing all that back out, then immediately restarting the process? No, you’re not. So, why is it that’s exactly what we think we need to do the second we stick a regulator in our mouth?? More than likely, right now you’re simply breathing IN and OUT, in not much more time than it took to read that sentence. Then, you’re NOT immediately inhaling. You’re pausing for a bit before you breathe again, in that fairly quick IN and OUT routine. How much of your lungs did you “fill?” Probably about half? Guess what? THAT is breathing normally. And THAT is exactly how you should be breathing on scuba. And, yes, we all know the #1 rule of scuba diving, but it’s perfectly okay to “hold” your breath on an EXHALE. There’s no gas in there to expand and cause injury, duh.

Think about how you’ve (probably) been breathing on scuba: that IIIIIIINNNNN and OOOOOUUUUUTTT pattern can cause HUGE buoyancy swings; maybe as much as a couple of feet in either direction, depending on your depth. Think about how much difficulty you may have had trying to get that perfect picture or navigate a tight swim-through with those kinds of buoyancy swings. Now, think about what “trimming out on empty” will do for you. It basically forces you to breathe normally. When you’re trimmed out perfectly neutrally on empty lungs, you know that a long inhale is going to cause you to rise, right? So you have to make a normal “IN/OUT” breath (get it in/get it out), and then you can pause as long as you want before breathing again. Normal breathing, just like you’re breathing right now. Not only will this technique improve your buoyancy, it just might also improve your gas consumption!

Now, this probably won’t come overnight, and it probably won’t feel natural to you at first. It takes a fair amount of discipline to change the way you breathe, especially if you’ve been diving for a while. It also takes a bit of discipline to learn (or remember) to hold still; in other words, don’t kick unless you need to go somewhere. If you feel that you need to kick to keep yourself from sinking, you’re NOT neutrally buoyant. Stop moving, hold still, then adjust for neutral buoyancy (with empty lungs). Now, do I think that what works great for me will automatically work great for you? Probably, yeah. If you’re willing to practice and give yourself a good handful of dives doing this before making up your mind, I think you’ll notice the benefits of Trimming Out On Empty to both your buoyancy and gas consumption. Drop me a line sometime to let me know how it’s working for you.

Until next time, never stop learning, never settle for “good enough,” and stay sharky, my friends!

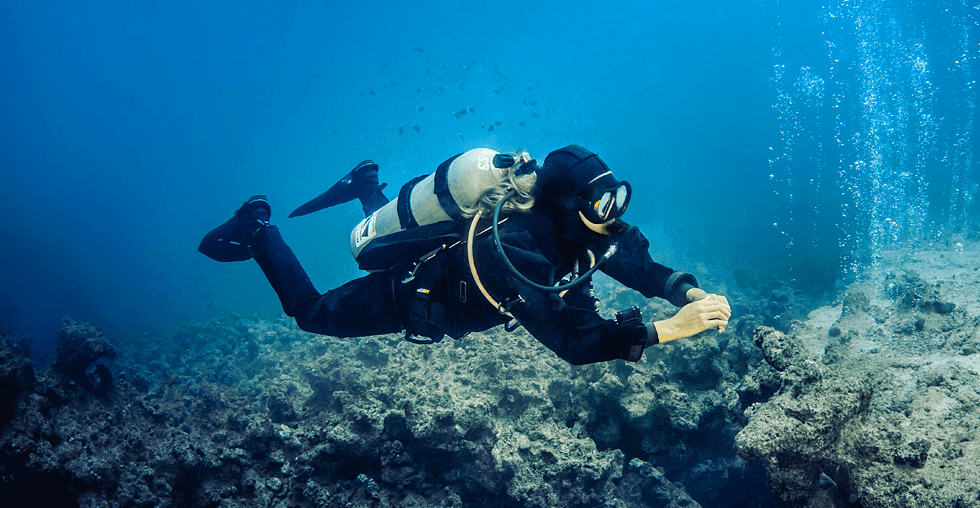

Don't Look Like This

This diver is almost vertical. Not only does this increase drag, but it puts the fins down. That creates problems with silting and kicking coral or other sealife, especially if using the flutter kick.

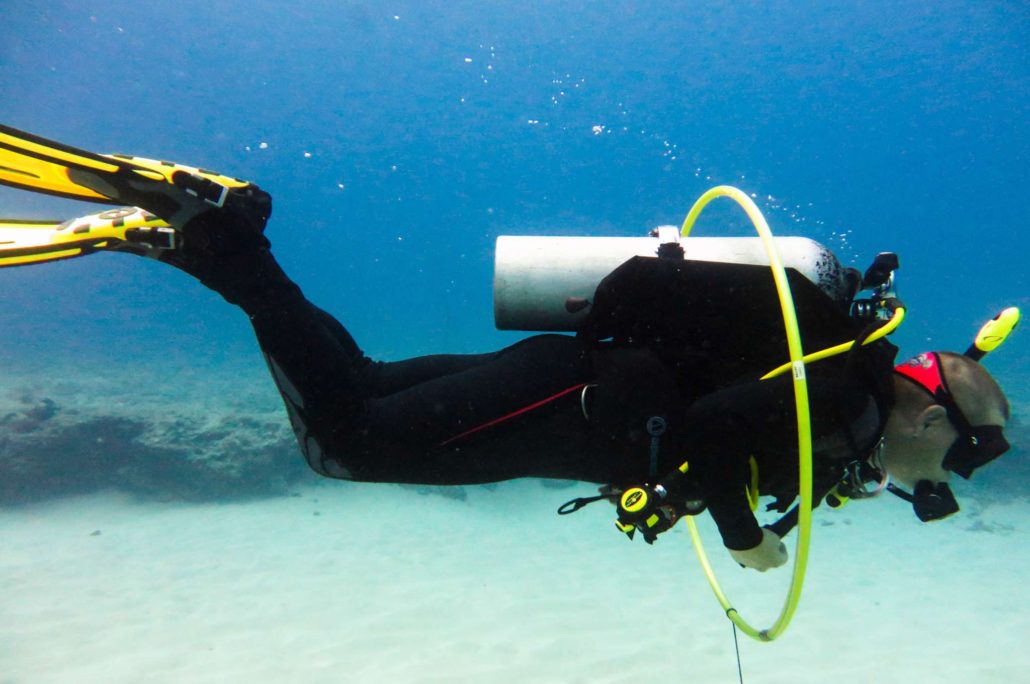

Look Like This

“Perfect trim” is certainly subjective, as different situations may call for different trim. But ideally, you should be as horizontal as possible, fins above the rest of the body, and not moving except for propulsion.

The Scuba Monkey

For the love of god, don’t look like this…

PPB

PADI’s Peak Performance Buoyancy course is certainly a step in the right direction.

0 Comments